The Writer Who Forever Changed the Way We Read and Write Today

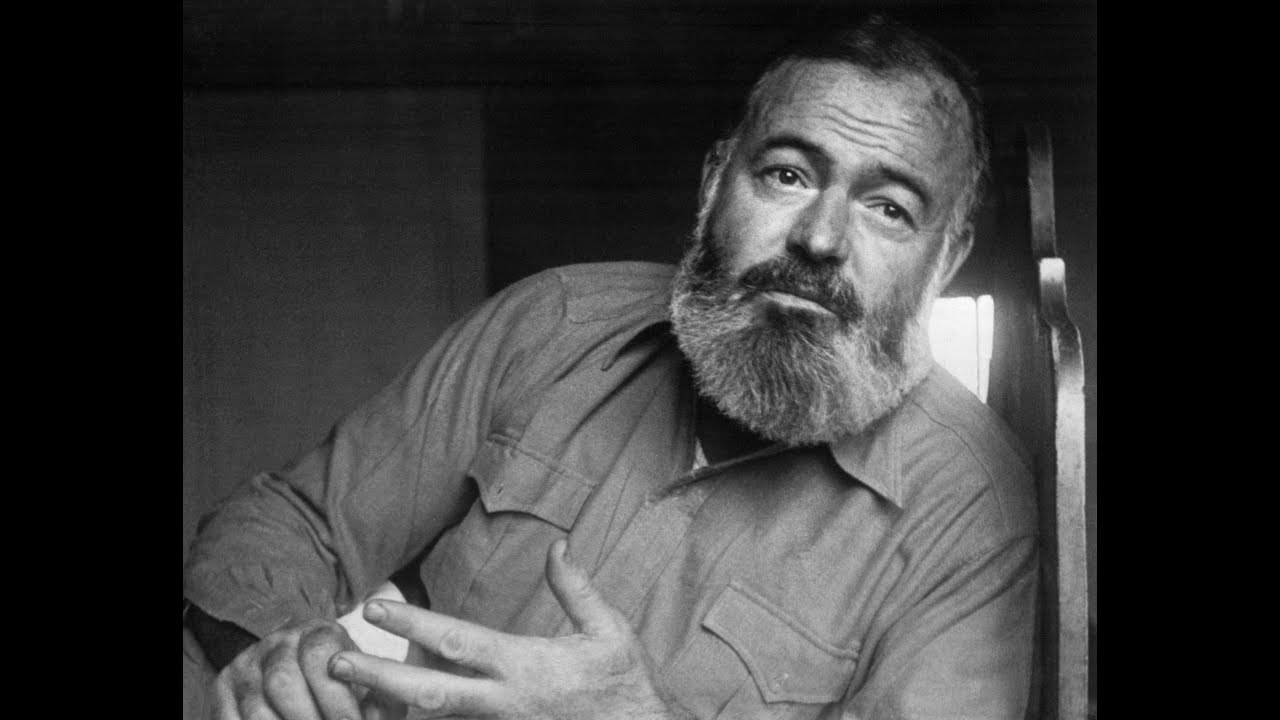

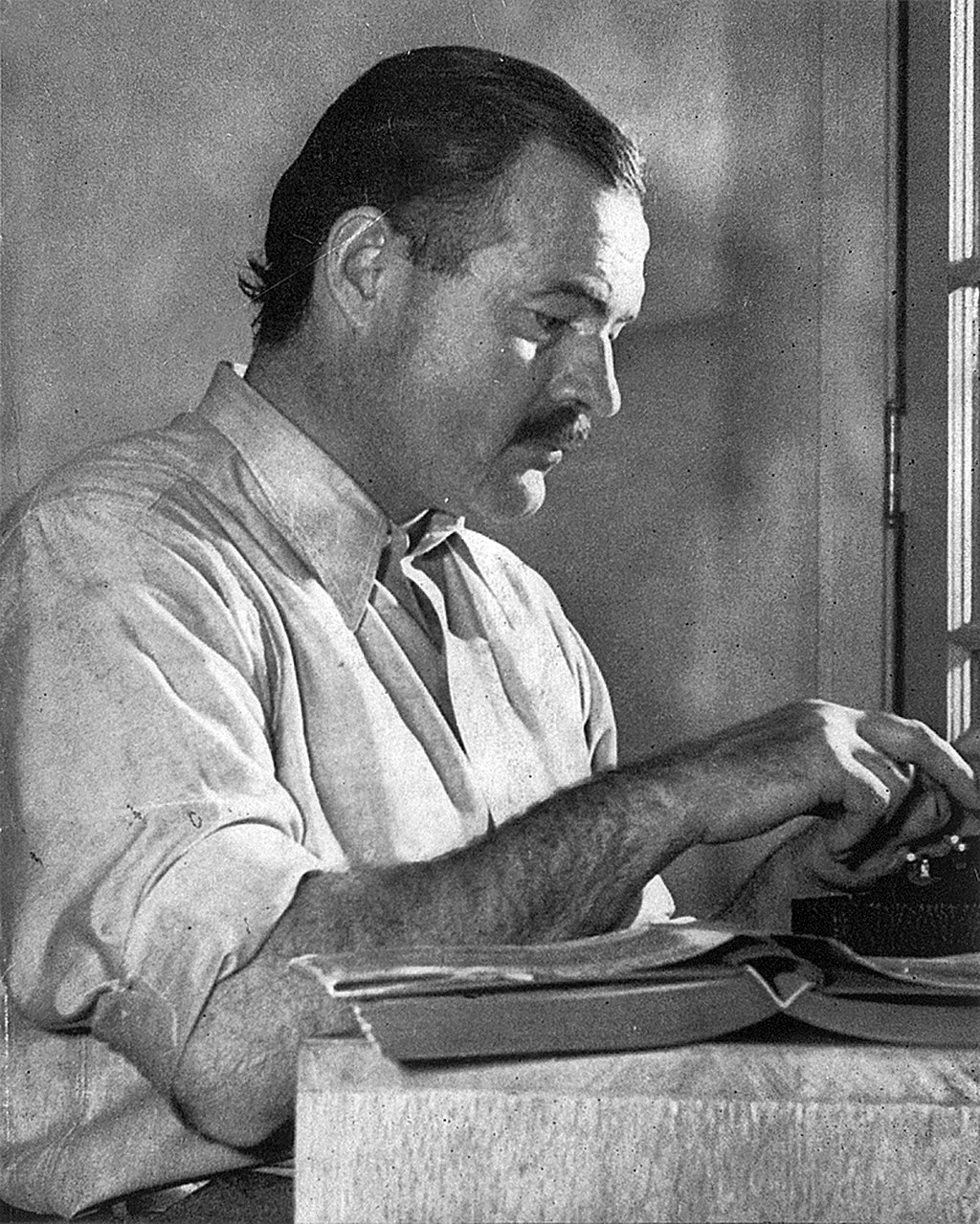

In terms of specific contributions that Ernest Hemingway made to American literature, the influence of his prose itself is a significant factor. The Nobel Prize committee couldn’t have said it better when they rewarded Hemingway “for his mastery of the art narrative…and for the influence that he has exerted on contemporary style” (The Nobel Prize in Literature 1954). It would be very hard for one to dispute the fact that Ernest Hemingway is the twentieth century’s most influential writer. One of the most influential aspects of Hemingway’s prose was his unique writing style, which he developed himself and which influenced many American writers thereafter. This is important because his writing style matched the newer fast paced life of post-war generations and influenced the next generations of writers that came after him. Not only that, but the way he lived his life and how he wrote about those experiences changed the way Americans read and write literature to this day.

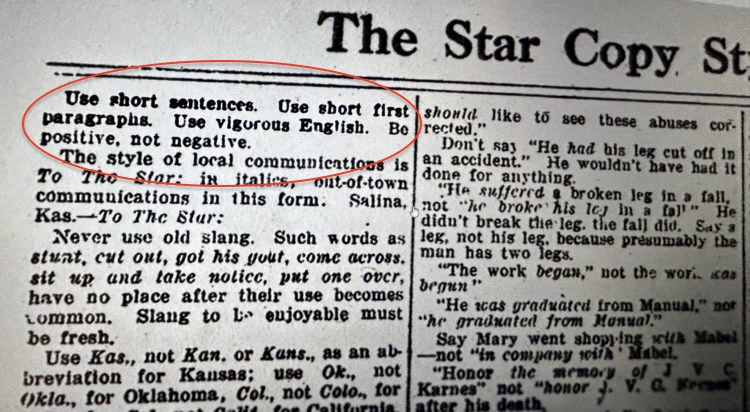

Hemingway wrote with short clipped sentence structure and very seldom did he use long compound sentences. Author Adam Sexton describes Hemingway’s style as having “an emphasis on nouns and verbs rather than adjectives and adverbs” (Sexton). Unlike writers that came before him, Hemingway rarely used long flowery descriptions or went into long explanations about things, leaving a lot unsaid for the reader to deduce on their own from what he does put down onto paper. Hemingway began developing this style from his early experiences as a newspaper writer. In newspaper writing there is very little room to elaborate extensively about a subject; one must use space wisely while still getting the point across. Because space in a newspaper is limited, Hemingway, as a young journalist, “had to focus his newspaper reports on immediate events, with very little context or interpretation” (“Iceberg Theory”). This brings to mind the saying, “Just the facts, ma’am, just the facts.” Hemingway relied on the use of short sentences as part of his journalistic style. An example from A Farewell to Arms of his short sentence style is: “The next year there were many victories” (Hemingway, chpt. 2).

There were rare times that Hemingway would deviate from this short sentence usage, but he didn’t do it often. When he did use long sentences, they consisted of short phrases and clauses connected by conjunctions. One example of this from A Farewell to Arms is as follows, (with conjunctions italicized): “The mountain that was beyond the valley and the hillside where the chestnut forest [grow] was captured and there were victories beyond the plain on the plateau to the south and we crossed the river in August and lived in a house in Gorizia that had a fountain and many thick shady trees in a walled garden and a wistaria [sic] vine purple on the side of the house” (Hemingway, chpt. 2, italics added). It’s as if he is stringing many short sentences together into a longer one to give specific passages a continuity, fluidity, and connection of collective ideas. He did not do this often, but when he did it was for a reason and it was indicative of his style.

Besides the short, concise journalistic influences for Hemingway’s writing, another influence of his style is the distinct modernist’s rejection of the elaborate writing style of 19th-century literature. The desire of these modern writers, according to literary critic Henry Louis Gates, is to create a style “in which meaning is established through, dialogue, through action, and silences—a fiction in which nothing crucial—or at least very little—is stated explicitly” (as qtd. in Putnam). Hemingway polished this unique writing style as he began to write his short stories, retaining his “minimalistic style, focusing on surface elements without explicitly discussing underlying themes” (“Iceberg Theory”). Hemingway himself referred to his pared-down, pruned writing style as the “iceberg theory,” which some refer to as the “theory of omission.” The theory of omission, which Hemingway pioneered, is based on his belief that the true meaning of a piece of writing should not be evident from the surface story but, rather, the crux of the story lies below the surface and should be allowed to shine through “between the lines.” Hemingway called this theory the “iceberg theory” because the theory is based on the premise that only a small part of an iceberg is visible to the naked eye above the water, while a much larger part of the iceberg is actually under the water. As every wise seaman knows, one doesn’t have to see the whole iceberg to know that there’s much more to it under the surface. The same is true for Hemingway’s narratives because only the bare facts are stated and visible while much is left unsaid under the surface.

Hemingway himself referred to his pared-down, pruned writing style as the “iceberg theory,” which some refer to as the “theory of omission.”

In Death in the Afternoon, Hemingway explained his “iceberg theory” this way, “If a writer of prose knows enough of what he is writing about, he may omit things that he knows and the reader, if the writer is writing truly enough, will have a feeling of those things as strongly as though the writer had stated them. The dignity of movement of an iceberg is due to only one-eighth of it being above water. …” (Hemingway). So essentially, the writer writes about the things “above the water” (the top of the iceberg that is visible), or the essential facts relative to telling the story, but writes in such a way that the reader can intuit that there is a whole bunch of the iceberg (or the story) still beneath the water that is being said without the author having to actually say it. With this writing style, Hemingway didn’t think it was necessary to write what the reader already understands, and he gives credence to assuming that the reader is educated enough to figure out things on their own by reading between the lines and using their intuition. That is the genius of Hemingway’s writing, he doesn’t need long drawn-out explanations and extensive text to get his point across in his stories. Because of this writing style, his stories move quickly and propel the reader along rapidly as they read so they don’t have time to get bored by unnecessary text. On the other hand, to some, it can seem that his writing is devoid of much feeling or sentiment because of this writing style. Both opinions are relevant; while many readers love that Hemingway’s stories move along at a fast pace and drive the reading along quickly, a reader can also miss some of that sentimentality that gives a story emotion.

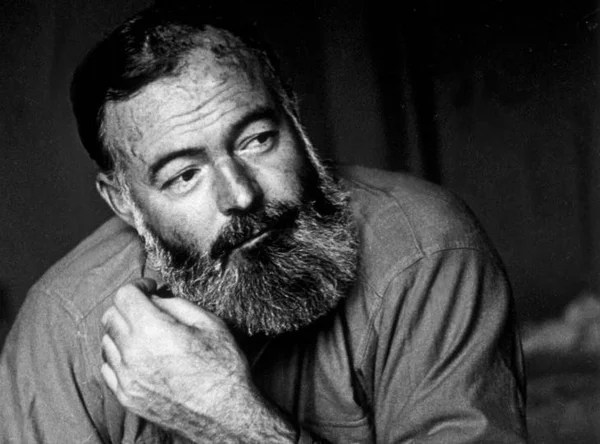

The renowned author lived what he wrote.

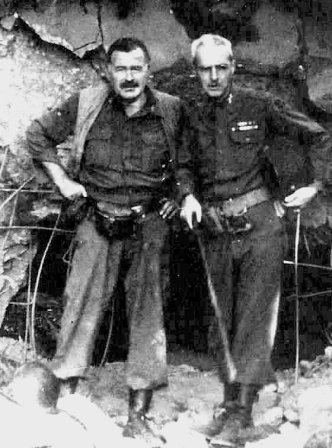

Hemingway with Col. Charles “Buck” Lanham in Germany during the fighting in Hürtgenwald in 1944, after which he became ill with pneumonia.

Another important aspect of Hemingway’s writing style is the fact that he didn’t just write romanticized versions of what he imagined life to be, he actually lived what he wrote. He lived, loved, and adventured hard and then he wrote about every aspect of those experiences, including the good, bad, and the ugly in his prose. WWI had brought about a disillusionment for people of the age, a disillusionment of the rosy, romanticized version of war that European literature had put forth juxtaposed with the more accurate reality of the horrors of war. Hemingway wrote about those realities in his book A Farewell to Arms which opened up American’s eyes to what war was really like. “The disillusionment that grew out of the war contributed to the emergence” of modernist writers like Hemingway (Nagel). Modernism is “a genre which broke with traditional ways of writing” and Hemingway, in a modernist way, “discarded romantic views of nature,” war, and life and wrote about them as he lived them (Nagel).

“The art of Manliness”

(The Hemingway code).

In the summer of 1932, Hemingway went to Cuba with two friends from Key West: Joe Russell and Joe Lowe. They went to fish the annual Marlin run aboard a boat called “Anita”. They also had a Cuban that they hired onboard to rig baits.

The Hemingway code was the male idea of honor, courage, and endurance of the times. It wasn’t just a set of values that Hemingway invented for the characters in his books, he actually lived that life and tried to embody those ideals in the way that he lived; then, he wrote about those experiences. He “hunted in the American West and in Africa, fished the Gulf Stream of Cuba and Florida, and covered the Spanish Civil War as a correspondent” (Nagel). All of this impacted Hemingway’s writing style, which was then emulated in the writings of subsequent authors who came after. “His own great impact on other writers came from his deceptively simple, stripped-down prose, full of unspoken implication, and from his tough but vulnerable masculinity…” (Dickstein).

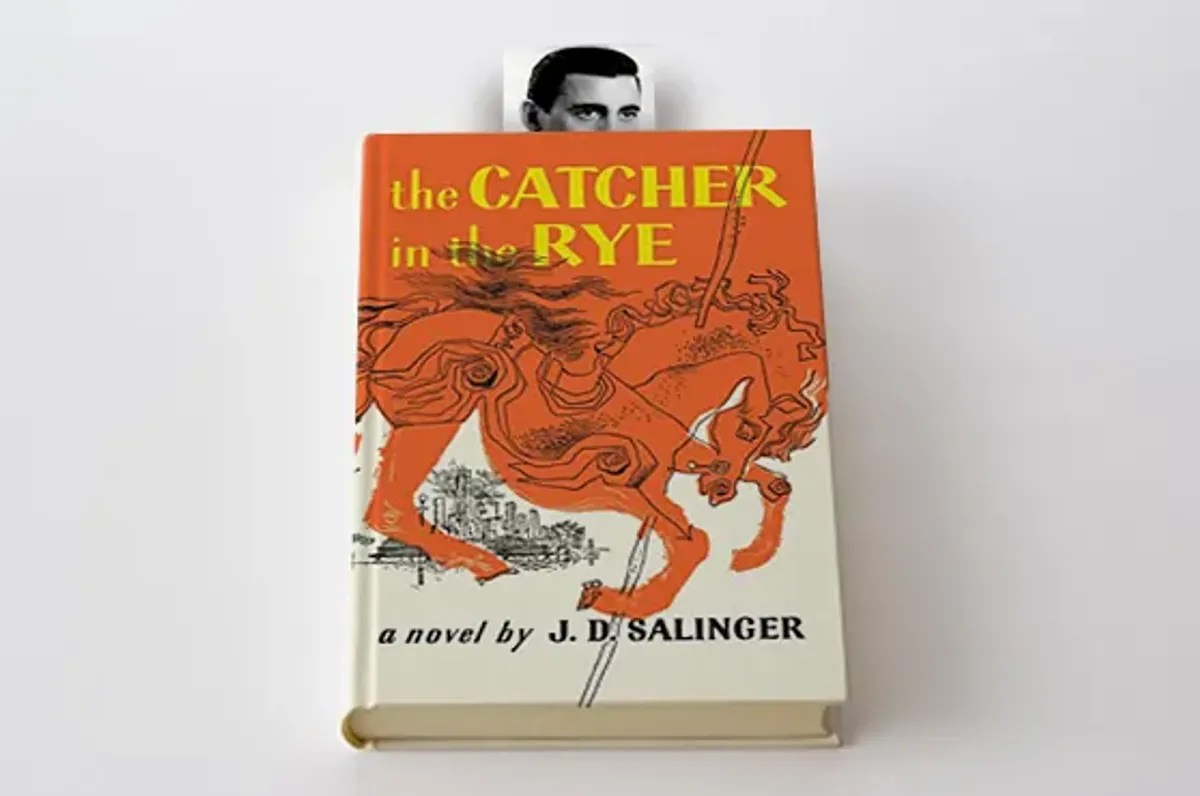

Hemingway represented the Indiana Jones figure, but he didn’t just represent it, he lived the life of a hard-living, tough, rugged adventurer and lived to write about it in his novels and short stories. This had an impact on subsequent writers, as the romanticized fantasy style of writing was done away with and the new realistic version of events, lived and then written about, became the new standard narrative. As Russell Banks put it, “Men writing in America have to contend with the shade of Hemingway, and the longstanding tradition of manliness he tried to represent. They may reject that tradition but they can’t ignore it” (as qtd. in Mariani). One author influenced by Hemingway is J.D. Salinger, “who named himself ‘national chairman of the Hemingway Fan Club’” (Mariani). Salinger, who wrote Catcher in the Rye “is said to have wanted to be a great American short story writer in the same vein as Hemingway” (“Ernest Hemingway”). Indeed, “the influence of Hemingway’s writings on American literature was considerable and continues to exist today.” (“Ernest Hemingway’).

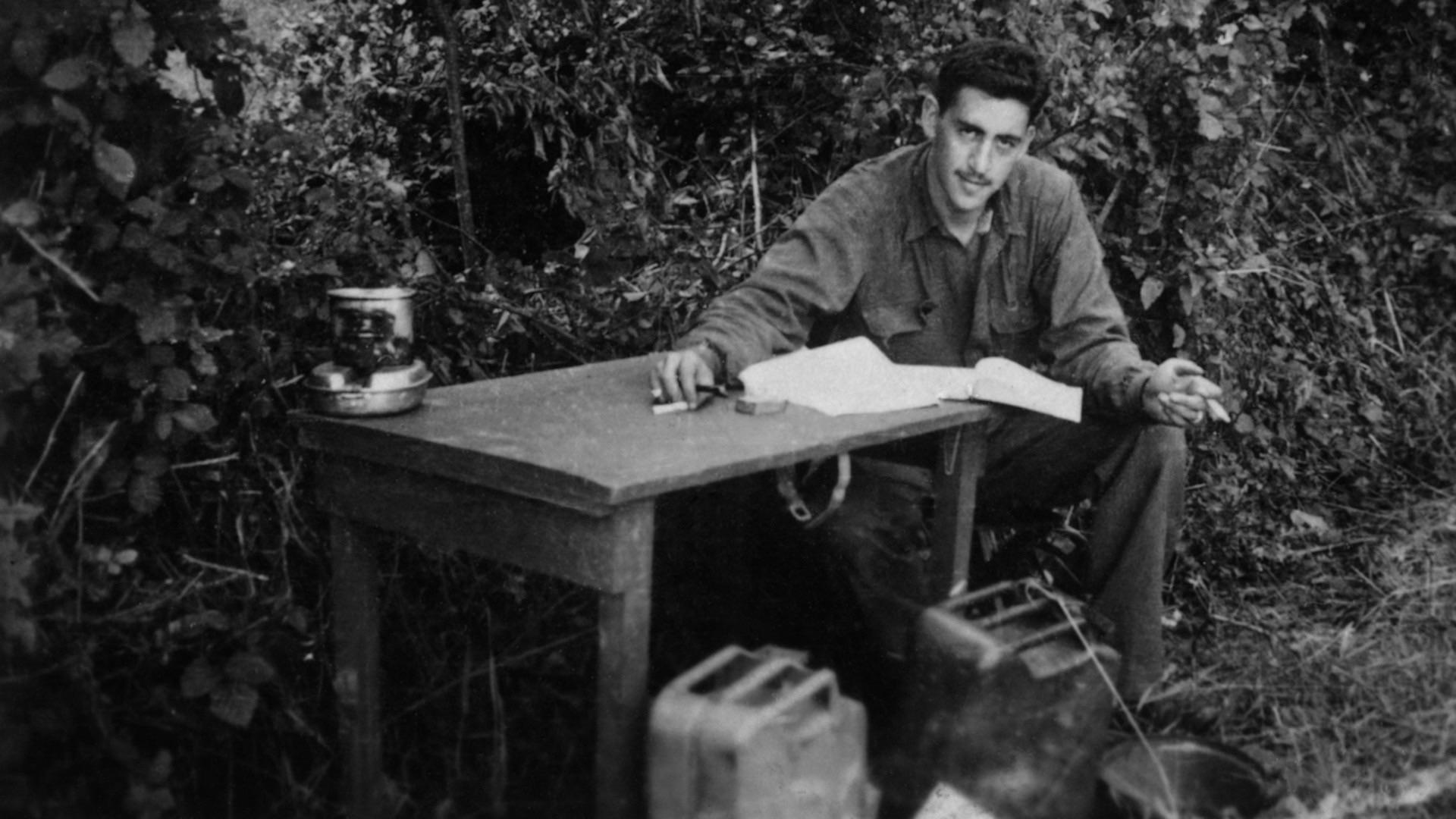

Hemingway and J.D. Salinger

Hemingway was a well-known literary giant and J.D. Salinger was a soldier when the two met during the liberation of Paris in 1944. Each admired the other’s writing and shared an aversion to long, drawn out narratives.

Another author known to be inspired by Hemingway’s terse prose is American freelance journalist and novelist Chuck Palahniuk, author of Fight Club. Palahniuk has a minimalistic approach to writing much like Hemingway’s style. Much like Hemingway, his writings use “short sentences” and he “prefers to write verbs instead of adjectives” (“Chuck Palahniuk”). Another is Canadian author and journalist Douglas Coupland who seems to have a dislike for long narrative prose, just as Hemingway did. Coupland explains, “reading fiction on Kindle of a book is just like, ‘oh, get to the point.’ It’s not fast enough.” Author Adam Kuo speculates that Canadian American author and poet Jack Kerouc was influenced by Hemingway. He explains, “Kerouac’s own words indicate that the term ‘Beat Generation’ came about from a contemplation on ‘the meaning of the Lost Generation.’ If Hemingway had not written The Sun Also Rises, it is quite possible that there would not have been a ‘Beat Generation,’ because the proper noun ‘Lost Generation’ would not have existed for…Kerouac to think about.” There is no forseeable end to the many modern-Hemingway inspired writers. To list them all would be impossible because “the influence of Hemingway’s style was so widespread that it may be glimpsed in most contemporary fiction, as writers draw inspiration either from Hemingway himself or indirectly through writers who consciously emulated Hemingway’s style” (“Ernest Hemingway’).

Hemingway was influential in changing the writing style from long, lyrical, drawn out, descriptive narratives of the European influenced romanticism movement, which romanticized such things as war, to a more direct, succinct writing style of American literature, indicative of the modernist literary movement. He developed the structure for “iceberg theory” which changed the writing style of American writers from that point forward. He brought attention to real experiences through his writing and made the reality of war and life available to the reader in such a way that had never been done before, developing the archetype for the Hemingway code that gave direction and meaning to living a heroic life based on real, reachable and attainable goals. “Hemingway’s legacy to American literature is his style,…he became the spokesperson for the post-World War I generation, having established a style to follow” and he significantly “changed the nature of American writing” from that time forward (Nagel). One observer speculates, “It would be impossible…to find any [other] major American author whom so many others have credited with influencing their styles” (Mariani). His clipped prose and concise writing style were needed to keep up the with the newer, faster pace of American life that came with the urbanization of America, and its emergence from isolation and entry into the first World War. Thankfully, his short, trimmed narrative style influenced American writers from that time on and changed the way American’s read and write to this day. Indeed, Hemingway “changed the way we write and read literature, and he changed it forever” (Sexton).

WORKS CITED

“Chuck Palahniuk.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 25 Nov. 2021. Web. 27 Nov. 2021.

Dickstein, Morris , Giles, James R. and Blair, Walter. “American literature”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 18 Aug. 2021, https://www.britannica.com/art/American-literature. Accessed 8 December 2021.

“Ernest Hemingway.” New World Encyclopedia, . 17 Jan 2021, 00:45 UTC. 27 Nov 2021, 02:04 <https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/p/index.php?title=Ernest_Hemingway&oldid=1048006>.

Hemingway, Ernest. A Farewell To Arms. Vintage Classics, 1999.

Hemingway, Ernest. Death in the Afternoon. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1960. Print.

“Iceberg theory.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 21 Nov. 2021. Web. 27 Nov. 2021

Mariani, John July. “On the Art and Influence of Hemingway’s Short Stories.” Literary Hub, Grove Atlantic and Electric Literature, 3 Apr. 2019, https://lithub.com/on-the-art-and-influence-of-hemingways-short-stories/.

Nagel, James. “Ernest Hemingway.” American Novelists, 1910-1945. Ed. James J. Martine. Detroit: Gale, 1981. Dictionary of Literary Biography Vol. 9. Literary Sources. Web. 15 Sept. 2016. https://homepages.uc.edu/~enzerch/reviews/sun04.html

Putnam, Thomas. “Hemingway on War and Its Aftermath”. Prologue Magazine, Spring 2006, Vol. 38, No. 1. Electronically published August 15, 2016, archives.gov. https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2006/spring/hemingway.htmlLinks to an external site.

Reid, Kelton. “How Bestselling Author Douglas Coupland Writes.” The Writer Files: Writing, Productivity, Creativity, and Neuroscience, Writer Files FM, 8 May 2018, https://writerfiles.libsyn.com/how-bestselling-author-douglas-coupland-writes.

Sexton, Adam. CliffsNotes on A Farewell to Arms. 15 Jul 2021. </literature/f/a-farewell-to-arms/book-summary>

The Nobel Prize in Literature, 1954. NobelPrize.org. Nobel Prize Outreach AB 2021. Fri. 26 Nov 2021. <https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/literature/1954/summary/>

“The world breaks everyone and afterward many are strong at the broken places.”

Ernest Hemingway, A Call to Arms

Lynne Hathaway

Lynne is an essayist and wordsmith with substantial knowledge of literature, literary criticism, proofreading and editing. She has a BA in Professional Studies with a minor in English and also has experience in Graphic Design.

Modern_Inklings@icloud.com

Do you prefer literature to have detailed descriptions and dialogues, or do you prefer pared down writing that allows you to “fill in the blanks” like Hemingway prefers? Why?

Share your creative thoughts in the comments box below. (Please remember to be respectful and kind!)

Leave a comment